Status Assessments of the Southern Hog-nosed Snake, Florida Pinesnake, Short-tailed Kingsnake, and Eastern Diamond-backed Rattlesnake in Florida

We conducted Florida status assessments for the southern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon simus), short-tailed kingsnake (Lampropeltis extenuata), Florida pinesnake (Pituophis melanoleucus mugitus), and eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus), all of which have been petitioned for federal listing as threatened. By perusing museum collections and various databases, conducting drift-fence and road surveys, and soliciting sightings via webpages, we compiled recent records (2000−2016) for the species. We compiled 183 recent records of the southern hog-nosed snake from 21 counties and 37 conservation lands (53% of records), 91 recent records of the short-tailed kingsnake from 11 counties and 18 conservation lands (70% of records), 451 recent records of the pinesnake from 45 counties and 97 conservation lands (68% of records), and 1,663 recent records of the diamond-backed rattlesnake from 66 counties and 345 conservation lands (78% of records). We used many of these records to create potential habitat models using MaxEnt, which provided the acreage of potential habitat by county and conservation land. The three nonvenomous species are primarily restricted to xeric upland habitats, particularly sandhill, whereas the rattlesnake is more of a habitat generalist. All species except the short-tailed kingsnake are found in some ruderal habitats, such as old fields and semi-improved pastures. Ocala National Forest and Withlacoochee State Forest have the most high-quality potential habitat in the peninsula for all four species, whereas Eglin Air Force Base has most high-quality habitat in the panhandle for the three species that occur there. The proportion of high-quality potential habitat within each species’ range that occurs on conservation lands was 28% for the southern hog-nosed snake, 43% for the short-tailed kingsnake, 44% for the pinesnake, and 35% for the diamond-backed rattlesnake. The southern hog-nosed snake is still locally common on the Brooksville Ridge, uplands along the Suwannee River, and on Eglin Air Force Base, but populations are apparently scarce or extirpated in counties at the southern extent of its range. Little is known regarding the fossorial short-tailed kingsnake, but populations appear to remain abundant on the Brooksville Ridge and in Ocala National Forest, but only one recent record exists from the southern half of its range. The pinesnake still occurs over much of its historical range but has always been uncommon or absent from the southern peninsula because of unsuitable habitat. Little information is available on abundance, but we trapped 31 pinesnakes along drift fences. Recent records are lacking from counties along the northern Atlantic Coast. The diamond-backed rattlesnake still occurs throughout its historical range, including parts of the Florida Keys, but populations have been extirpated from some large urban areas, particularly in the southeastern peninsula.

Primary threats to these species are habitat loss, habitat degradation (e.g., fire suppression and silviculture), and road mortality. Sufficient habitat is present on public lands for long-term conservation of all four species, provided habitats are properly managed (e.g., prescribed burning of pinelands) and road construction is limited. However, >55% of high-quality habitat identified for all four species occurs on private land, and this figure is >70% for the southern hog-nosed snake. Populations of the endemic short-tailed kingsnake apparently persist in subdivisions with native ground cover and in fire-suppressed sandhill habitat, but the paucity of recent records from highly fragmented habitats (mostly scrub) in the southern half of its range is cause for concern.

INTRODUCTION

The southern hog-nosed snake (Heterodon simus), short-tailed kingsnake (Lampropeltis extenuata), Florida pinesnake (Pituophis melanoleucus mugitus), and eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake (Crotalus adamanteus) are upland snake species whose populations are suspected to be declining in Florida (Timmerman 1994, Tuberville et al. 2000, Timmerman and Martin 2003). In 2012, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) was petitioned by the Center for Biological Diversity to list all 4 species as Threatened (Adkins Giese et al. 2012, USFWS 2012). Recent systematic surveys have not been conducted for these species, and current occurrence information is scarce. The Florida pinesnake is currently listed in Florida as a Species of Special Concern and will be reclassified as Threatened once the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission’s (FWC’s) Imperiled Species Management Plan is approved. The short-tailed kingsnake is already listed as state Threatened. In 2013, the USFWS provided funds to the FWC and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources to assess the status of the three snake species found in both states, and FWC opted to also assess the status of the endemic short-tailed kingsnake.

Habitat destruction and degradation are partially responsible for declining upland snake populations, but road mortality and human persecution of snakes, particularly of rattlesnakes, are contributing factors (FWC 2011b, 2011c, Timmerman and Martin 2003). The three nonvenomous species occur in xeric upland habitats that historically were primarily longleaf pine (Pinus palustris) sandhills, but the eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake occurs in a variety of upland, mesic, and even hydric habitats. Florida has experienced substantial loss of scrub and sandhill habitats from urbanization, agricultural clearing, and mining. It is estimated that over 97% of the original longleaf pine ecosystem has been lost due to habitat conversion (Noss et al. 1995). From 1985 to 2003 (a period of 18 years), 15.5% of Florida’s sandhill habitat and 12.4% of its scrub habitat were converted to other uses, primarily urban or other developed uses (Kautz et al. 2007). Only 12% of Florida’s original sandhill habitats remain (Florida Natural Areas Inventory 2011), and many of the remaining habitats are degraded by fire suppression and invasive species, and they have been fragmented by roads and human-altered habitats (FWC 2011a). In fragmented habitats, roads can be a major source of mortality for snakes (Enge and Wood 2002) and result in altered behavior and road avoidance (Andrews et al. 2005, 2008). Rattlesnakes and other snake species are often killed intentionally by people out of fear, and some species are harvested for the skin or pet trade (Enge 2005a, b). Although little population data exist for these species, anecdotal observations and comparisons of historical versus recent records (Krysko et al. 2011) suggest that some species have been extirpated from historical localities. This project was initiated to determine the current occurrence of these upland snake species in Florida, particularly on public conservation lands, in order to provide some of the information needed for federal and state status assessments—almost 30% of Florida’s terrestrial land area is protected on federal, state, or local conservation lands. We used common and scientific names of amphibian and reptile species according to the latest Peterson Field Guide (Powell et al. 2016). Upland Snake Status Assessments 6

Objectives

1. Determine the current status and occurrence of these four snake species in Florida.

2. Determine the detection rates of survey methods for each species.

3. Determine factors affecting species occupancy rates.

4. Use species occurrence data from field surveys and locality records to create statistically predictive models and maps.

Southern Hog-nosed Snake

Adults are typically 45–55 cm total length (TL) with a maximum TL of 61 cm. Breeding occurs primarily in May and June but has been reported from mid-April through August (see Ernst and Ernst 2003). Eggs are usually laid in July and hatch in ≈60 days in September–October (Jensen 1996). Clutch size is 6−19 eggs (Palmer and Braswell 1995, Enge 2004). Hatchlings measure 13.4–18.0 cm TL (see Ernst and Ernst 2003). We have records from every month in Florida, but 33.3% of 267 records came from May–June during the breeding season. The other peak was in October–November (34.5% of records), which primarily represented hatchlings. During a pedestrian survey in Hernando County, most snakes were found in June and October–November, with 96% of snakes in October–December being hatchlings (Enge and Wood 2003). Peak activity was May–June and October in South Carolina (Gibbons and Semlitsch 1987, Tuberville et al. 2000) and September–October in North Carolina (Beane et al. 2014). The strong fall activity peak for 764 snakes found in North Carolina was probably because observers were good at detecting juveniles on roads; historical records indicate fall is also the most productive time of the year to road cruise for this species in Florida, particularly juveniles. Hatchlings and juveniles comprise a large proportion of the population, and adult females appear to be particularly prone to mortality (Beane et al. 2014).

The southern hog-nosed snake eats various anurans, lizards, and even small mammals (see Ernst and Ernst 2003). It probably excavates most of its prey from burrows ≤11.5 cm deep (Goin 1947). In North Carolina, eastern spadefoots (Scaphiopus holbrookii) and six-lined racerunners (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) were the primary prey items, but only juveniles contained lizards. Juveniles also occasionally fed upon large invertebrates (Beane et al. 2014). This species is diurnal, with peak activity from 1000 to 1400 hr (Beane et al. 2014). In Florida, we have records from 0900 to 1900 hr. They are good burrowers and have been found brumating up to 46 cm deep in firmly packed sand in North Carolina (Palmer and Braswell 1995). Many snakes found crossing roads freeze when approached or slowly crawl away, sometimes using a hesitant, jerky motion. If picked up, a snake may feign death, but this species is less prone to this defensive behavior than the eastern hog-nosed (Beane et al. 2014). Most snakes only hiss, flatten their necks, and hide their heads under a coil, but some will thrash, gape, and roll over (Myers and Arata 1961).

Short-tailed Kingsnake

This extremely slender species measures up to 65.5 cm TL. No reproductive information exists for this poorly known species. It eats mostly small, smooth-scaled snakes, particularly Florida crowned snakes (Tantilla relicta) (Carr 1934, Mushinsky 1984, Rossi and Rossi 1993), Upland Snake Status Assessments 7 but a few have eaten small lizards in captivity (Allen and Neill 1953, Ashton and Ashton 1981). One snake contained a nonnative Brahminy blindsnake (Indotyphlops braminus) (Godley et al. 2008). Prey may be killed by constriction, but larger snake prey may escape even after 2 hr of constriction (Mushinsky 1984, Rossi and Rossi 1993). It is primarily fossorial and has been dug up by farmers, gardeners, and builders (Van Duyn 1939, Highton 1956, Woolfenden 1962). Some have been found under fallen logs or other cover, including sphagnum moss (Carr 1940), and Ray Ashton observed one entering a gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus) burrow. It burrows by pressing its nose against sand and moving its head up and down (Woolfenden 1962). Once buried, it moves through sand using lateral undulations of the body. Most records are from April−May (23.3% of 146 records) and October–November (46.6%), which are apparently times of the year when it spends more time crawling on the surface during the day (Campbell and Moler 1992). In summer, it is primarily nocturnal (Highton 1956). When threatened, it often strikes repeatedly with its mouth closed while making a hissing sound. A disturbed individual will often cock its head sharply upwards and rapidly twitch it laterally, sometimes while elevating and slowly waggling its tail. The head-twitching behavior may mimic that of the pygmy rattlesnake (Sistrurus miliarius), which has a similar dorsal pattern and coloration, and the tail movements may mimic caudal luring by juvenile pygmies (Enge et al. 2015). The harlequin coralsnake (Micrurus fulvius) is a known predator (Highton 1956). One specimen reported on the FWC webpage was found in a swimming pool, and another one was trapped in a spider web on a lanai.

Florida Pinesnake

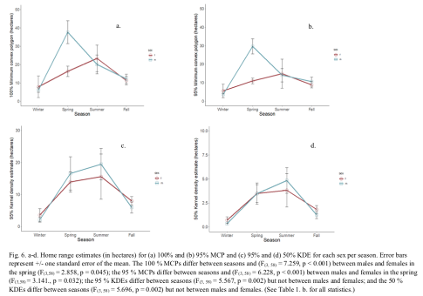

Adults are heavy bodied and typically measure 122–168 cm TL, with a maximum TL of 229 cm. Pinesnakes breed in April and May, laying very large, adherent eggs about 1 month later (see Ernst and Ernst 2003). Four clutches contained 4–8 eggs (Neill 1951, Franz 2005b), but the maximum clutch size could be nearer 14 eggs based upon the northern pinesnake (P. m. melanoleucus) (Zappalorti et al. 1983). Nest locations are unknown for the Florida pinesnake, but the northern subspecies digs nest burrows, and a black pinesnake (P. m. lodingi) nest from Mississippi was found at the bottom of a gopher tortoise burrow (Lee et al. 2011). The Florida pinesnake could also nest in tortoise or mammal burrows, including southeastern pocket gopher (Geomys pinetis) runways. Eggs typically hatch in 70–75 days in August or September (Ernst and Ernst 2003). Sexual maturity is reached in 3 years at 91 cm snout-vent length (SVL) (Franz 1992). We have records from every month of the year in Florida, but peak activity was in April–June (50.3% of 734 records) during the breeding and egg-laying season. Overall, 79.7% of records were in March–August and only 2.6% in December–February. Home-range sizes averaged 73.3 ha (range 32.5−139.7 ha) for males and 13.5 ha (range 10.6−16.9 ha) for females in Putnam County (Franz 2005). In southwestern Georgia, the mean home-range size was 70.1 ha (range 25.7–156.8 ha) for males and 37.5 ha (range 18.6–80.7 ha) for females (Miller et al. 2012).

Florida pinesnakes primarily feed on pocket gophers, other rodents, and rabbits (Sylvilagus spp.), but they also eat ground-dwelling birds and eggs (Ernst and Ernst 2003, Franz 2005, Miller et al. 2012). Young snakes may eat lizards. They are adept at excavating the sand plugs of pocket gopher burrows to access their runways (Franz 2001, 2005). Prey is usually Upland Snake Status Assessments 8 killed by constriction, but prey in burrows may be killed by pressing it against a wall. They are fossorial, spending ≈80% of their time in underground retreats, primarily pocket gopher burrows. Other retreats used are stump holes, mole runs, and burrows of gopher tortoises, nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinctus), and mice (Franz 2005, Miller et al. 2012). They are primarily active during the day but may exhibit crepuscular or nocturnal activity. Snakes occasionally climb into shrubs and small trees (Franz 2005) and have been reported sheltering in crevices of large oaks where burrows are absent in Sarasota County. A disturbed snake will coil, inflate its body, vibrate its tail, and hiss very loudly (facilitated by a flap across the glottis that vibrates) through a partially open mouth. Irate snakes may strike, but the mouth usually remains closed. This intimidating defensive display sometimes results in people killing pinesnakes because they are mistaken for rattlesnakes. Dogs occasionally kill adults, and a hawk (Buteo sp.) was seen carrying a snake ≈120 cm TL (Greene and Tracy 2011).

Eastern Diamond-backed Rattlesnake

Adults are typically 120−150 cm TL. Rattlesnakes are largely diurnal, primarily moving in the morning and late afternoon, although occasional movements occur after dark. In northern Florida, adults seek shelter underground in November, but on warm winter days they may move between shelters, which are often stumpholes of pine trees, gopher tortoise burrows, armadillo holes, and tip-up root systems (Timmerman and Martin 2003). Some snakes are on the surface near their overwintering shelters whenever temperatures are >18°C (Timmerman and Martin 2003). Emergence from burrows occurs in February and March in northern Florida. April (11.5% of 1,383 records) was second only to October (12.4%) in the number of records. In central Florida, snakes occupy burrows December−February (17.6% of records), but some are on the surface on all except the coldest days. In southern Florida, snakes are active year round and do not need burrows, often sheltering under saw palmetto (Serenoa repens) clumps (Timmerman and Martin 2003). Females breed and give birth to an average of 14 (range 8−29) live young in August and September. A female typically gives birth every other year, depending upon prey availability (Timmerman and Martin 2003). Males making long-distance movements in search of mates and dispersing neonates help account for 41% of records being in August−November. Many records, particularly from residential areas, were of neonates. Adults in such areas presumably have survived by being cryptic and seldom crossing roads. The diet consists primarily of mammals up to the size of cottontail rabbits (Sylvilagus floridanus) and fox squirrels (Sciurus niger), and occasionally ground-dwelling birds such as northern bobwhites (Colinus virginianus) (see Ernst and Barbour 2003). The diamond-backed rattlesnake is a classic sit-and-wait ambush predator that scent-tracks envenomated, paralyzed prey. It is a good swimmer; Lazell (1989) reported one seen floating ≈38 km off the southern coast of Florida.

Home ranges in the Tallahassee Red Hills were 80 ha for females and 200 ha for males (Means 1985), whereas the mean home-range size was 46.5 ha for females and 84.3 ha for males in northern peninsula sandhills (Timmerman 1995) and 120−260 ha in the Everglades (see Dalrymple in Timmerman and Martin 2003). Home ranges of males overlap. Summer daily movements average 13−25 m and increase in fall (Timmerman and Martin 2003). The propensity of snakes to rattle varies among individuals and situations. Snakes on the move or that feel exposed, such as on recently burned areas, are more prone to rattle and become Upland Snake Status Assessments 9 defensive without being provoked. Neonates may be killed by a variety of snakes, birds, mammals, and even large ranid frogs; adults have been killed by white-tailed deer, raptors, and feral hogs (Timmerman and Martin 2003).

METHODS

Locality Records

Initially, we compiled all known localities in Florida from 2000 through 2014 for the four target snake species using museum records, literature records, Florida Natural Areas Inventory (FNAI) records, Herpetological Education and Research Project records (http://www.naherp.com/), and unpublished survey databases. During the study, we solicited additional records by e-mailing public land managers and biologists from federal, state, and county agencies; herpetologists and snake enthusiasts; nuisance snake trappers; environmental consultants; and large private landowners and private landowner organizations. We prepared FWC media releases advertising two FWC webpages. We also advertised the webpages using several flyers and posters (Fig. 1) that were e-mailed to land managers for posting in kiosks, offices, and nature centers. One webpage (https://public.myfwc.com/fwri/raresnakes/) was for reports of southern hog-nosed, Florida pine, and short-tailed kingsnakes (Fig. 2). A photograph typically had to be included as verification of species identification before we entered the record in the Excel database. The second webpage was for reports of eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake reports (https://public.myfwc.com/FWRI/DRS/); documentation photographs were requested, although we ultimately included most observations in the Excel database as we assumed that most persons could identify this distinctive species.

The Excel database included the area (name of conservation land or “private land”), year and month of sighting, coordinates of sighting, accuracy of location (high, medium, or low [see below]), credibility of sighting (voucher [see below] or credible observer), name of reporter and affiliation (if any), and comments. “Voucher” refers to a specimen deposited in a museum collection or a vouchered photographed. We vouchered all photographs and specimens in the Florida Museum of Natural History (FLMNH) at the University of Florida, Gainesville. If a record came from within 1 km of the boundary of a conservation land, as determined by plotting the record using Google Earth and FNAI’s conservation land database, we recorded the conservation land followed by “near” in parentheses. Assignment of records to high, medium, or low locational accuracy was somewhat subjective. All records were considered to have “high” locational accuracy if a street address or a distance to the nearest tenth of a mile from a road intersection or landmark were provided; the coordinates came from a GPS unit or a cell phone or digital camera with GPS capability; or the coordinates provided by the mapping tool on the reporting webpages appeared to be accurate. Most records classified as having high locational accuracy were probably within 100 m of the snake’s actual location, but some might have been as far away as 500 m. Only these records were used when producing habitat models for each species. Some reporters failed to use the mapping tool on the webpage or used it incorrectly. We did not add records to the database if the report on the webpage lacked coordinates, unless it Upland Snake Status Assessments 10

represented the first report of the species for a particular conservation area. We also did not add records to the database if the webpage report had coordinates that we suspected were incorrect because the location did not correspond with comments provided by the observer. For example, a person might have reported finding the snake in their yard or on a road, but the location plotted in an uninhabited area. Persons providing suspect coordinates or no coordinates for the three nonvenomous species were usually contacted via email in an attempt to obtain an accurate location that could be included in the database. We received too many reports of diamond-backed rattlesnakes to follow up on records lacking coordinates or with suspect coordinates. Records were classified as having “medium” locational accuracy if the distance reported was to the nearest mile or the report came from a conservation land ≤250 ha in size; these records were probably accurate within 2 km of the snake’s actual location. Records with “low” locational accuracy were reports from large conservation areas or reports of distances to the nearest mile from cities, where the road information was not included (e.g., 2 mi SE of Gainesville). Many historical records were classified as having low locational accuracy.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would particularly like to thank our technicians Glenn Bartolotti, Steve Christman, and Cody Godwin who helped conduct road or drift-fence surveys. Houston Chandler and Dirk Stevenson with The Orianne Society developed the potential habitat model for the eastern diamond-backed rattlesnake, and James Bareens developed earlier potential habitat models for the other snake species. Carl Weathington developed the FWC webpages to report snake sightings, and Brittany Bankovich, Glenn Bartolotti, Anna Farmer, Garrett Craft, Steve Godley, Georgia Kratimenos, Alex Kelvy, Amanda Kubes, Paul Moler, and Jordan Schmitt provided database records. Bess Brown Harris, Travis Blunden, Adam Casavant, Robert Cuskley, Lauren Diaz, Carolyn Enloe, Anna Farmer, Allan Hallman, Sean McKnight, Paul Moler, Trevor Persons, Ellen Robertson, Jess Rodriguez, Rex Rowan, Claire Sundquist, and Travis Thomas assisted with drift-fence surveys. Anna Deyle, Kathleen Mahoney, Paul Moler, Matt Smith, and Zach West assisted with road surveys. Kenney Krysko vouchered records in the Florida Museum of Natural History. We thank Marcus Beard (ANF), Brian Camposano (JSF, TR), John Dunlap (ANF), Jennifer Perkins (CB), Joe Reinman and Terry Peacock (SM), and Carrie Sekarek (ONF) with providing permission to conduct drift-fence surveys or providing prescribed burn schedules.

|

snake poster.pdf Size : 8317.451 Kb Type : pdf |

Florida Pine Snake Study 2018-2019

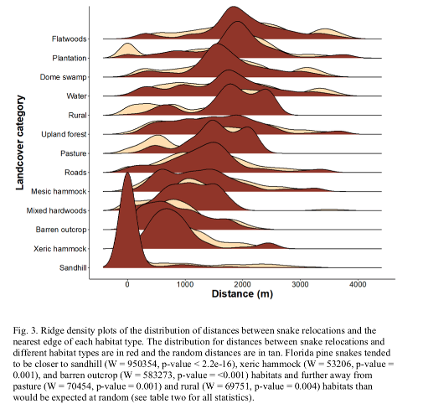

Florida pine snakes in our study preferentially selected sandhill (Fig. 3) and areas within wildlife environmental areas. Thus, a recommended conservation practice is to refrain from fragmenting large tracts of suitable habitat (FWC, 2018).

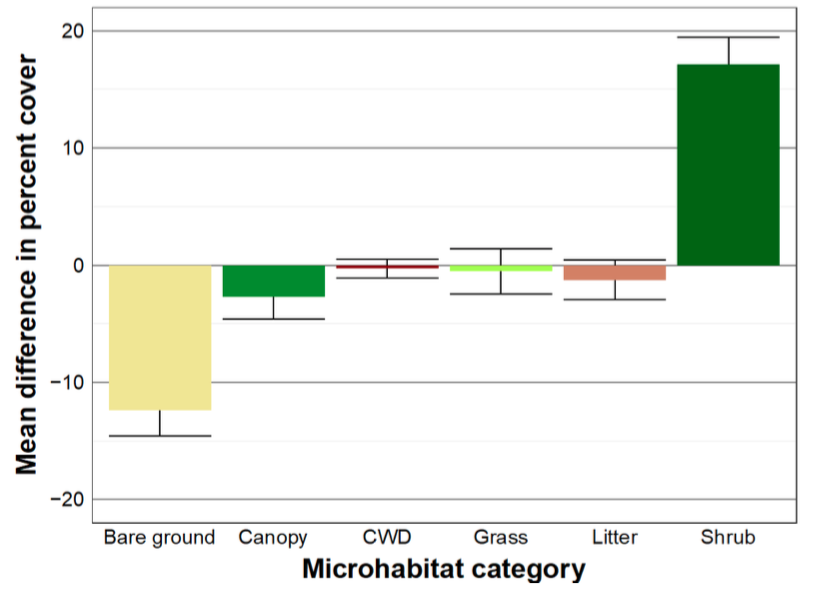

Florida pine snakes in our study preferentially selected for microhabitats (while basking) that included an open canopy, shrub coverage, and little to no bare ground Anecdotally, Florida pine snakes were often observed “backed” against the base of shrubs facing outward, which could maximize the balance between visual awareness and concealment. Habitat maintained for Florida pine snakes should include patches of shrub in open canopy to allow for protected basking sites.

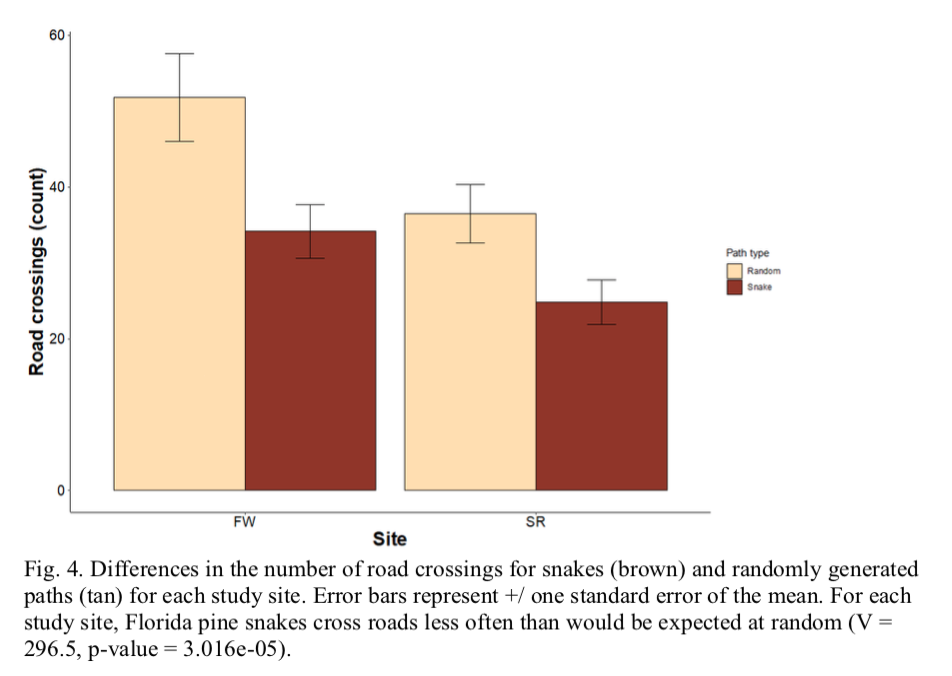

We found that Florida pine snakes cross dirt roads less often than would be expected at random at both study sites, though this could be an artifact of roads separating different habitat types, habitat maintained for Florida pine snakes should minimize road exposure. If road construction is necessary, unimproved dirt roads should be used to the maximum extent possible.

We show that observations of site fidelity in our populations of Florida pine snakes were highest during winter months suggesting that even in temperate climates such as northern Florida, winter refugia are utilized. Small mammal burrows, including those created by southeastern pocket gophers, are most often used as winter refugia, and gopher tortoise burrows are most commonly associated with observations of site fidelity in the spring. Together, these data suggest small mammal burrows provide characteristics (e.g., warmth), that are vital to surviving cooler temperatures, and larger sites (e.g. gopher tortoise burrows) may provide more adequate characteristics associated with breeding behavior. A recommended conservation practice is to avoid soil compaction or disturbance, especially in areas with southeastern pocket gophers or gopher tortoises, year-round, if possible. If soil compaction or other development activities must occur, it may be better to conduct those actions when Florida pine snakes are less likely to be dependent on specific refugia (e.g., summer). However, this recommendation should be weighed against the increased risk of mortality from vehicles or heavy equipment when Florida pine snakes are more active and making larger movements across the landscape.

Implications:

Florida pine snakes in our study preferentially selected areas within wildlife environmental areas (Fig. 14-15). Thus, our study reiterates the importance of large tracts of suitable habitat for maintaining Florida pine snake populations.

Our data highlight the variation in Florida pine snake abundance and home range size observed across sites. Although we were not able to determine the reason for this variation at our study sites, it could relate to resource abundance (e.g., prey abundance) and warrants further study.

My Florida Pine Snake Study Memoirs, May 2018-May 2019

Richard Orton helped me get up to speed on tracking instructions and we became good friends. He left in August to work on his PHD.

November 27th I met with Joe Prenger US Fish and Wildlife and Daniel Hipes Florida Natural Areas Inventory we had a great day. It was rather cold but there was two Pine snakes above ground in the upper 50s so made for a really good day. We had great discussion.

consistent with the one in this photo. I would assume these scars are from rodents caught in narrow burrows where the snake cannot constrict the rodent in the traditional way of wrapping loops of its body around them. Rodents are swallowed whole or pressed against the side of the burrow. It’s must be brutal down there!

In the field with Natalie Montero, Blair Hayman and Brooke Talley